Who made the monsters? A lesson from Del Toro's Frankenstein

Thanks for reading my free newsletter! If you’d like to support my work, you might consider buying or gifting HUMANS: A MONSTROUS HISTORY. Excellent free ways to support me include: borrowing HUMANS from your library or recommending they buy it; reviewing the book on Goodreads, Amazon, or Storygraph; adding it to your wish list or TBR list; or telling friends, family, colleagues, or students about it.

Hallo everyone and welcome, new subscribers!

First, two news items in case you missed them:

Would you like to join me online for my last event of the year? I’ll be talking about Humans: A Monstrous History on Thursday Dec 4, 7-8pm CST (8-9pm EST), hosted by the Linda Hall Library (Kansas City, MO). Register here! To convert the time to your time zone enter your location in the “add location” box in this time zone converter.

My latest byline is an essay in Smithsonian about a 16th-century painting of hell which linked Satan and his demons to the New World beyond Europe. For more essays, do visit my website.

Who made the monsters?: A lesson from Del Toro’s Frankenstein

The genius and the mass shooter have something in common: each is typically framed as acting alone. Yet both have enablers and catalysts: people, circumstances, and structures that make their actions possible.

The genius props up the myth, now somewhat diminished, that the West invented science: ‘great white men’ with neither assistants, colleagues, nor interlocutors and who supposedly created knowledge where there had been none before. Similarly the myth of the mass shooter as a lone wolf frames them as springing, if not entirely from nowhere, then from an alignment of nature and circumstance that is impossible to predict, absolving society of responsibility.

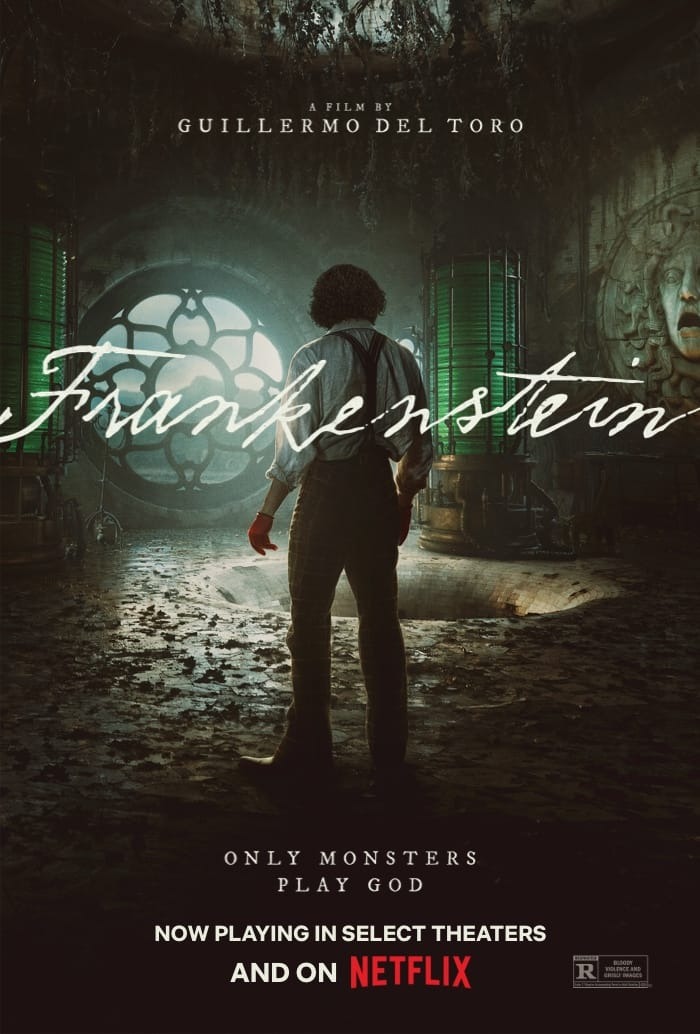

Modern adaptations of Frankenstein typically humanize the Creature and demonize his creator, obscuring Shelley’s more ambiguous framing of both. Guillermo del Toro’s captivating Frankenstein takes a middle position that shifts some responsibility onto a third group: the rest of us.

Look not at the monsters but at their enablers and storytellers, for they are the real monster-makers.

As I wrote in Humans: A Monstrous History, ‘monster’ simply means category-breaker: a being who straddles or transcends categories (like dead and alive), or falls outside the parameters of normal according to a particular system of classification. A category-breaker isn’t necessarily frightening or fictional even if people today tend to relegate them to the spooky corners of the bookcase.

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the verb ‘to monstrify’ – ‘to make monstrous; to distort, pervert’ – to the turn of the seventeenth century and to the French monstrifier. Both spring from the Latin monstrum (to show or to warn). This rare verb seems to have fallen out of use a century later. Yet monstrification is still an apt word for the process of inventing stories about who or what supposedly isn’t normal or typical.

Today, sometimes individuals are framed as monsters (with or without that word) for breaking the social contract in profound ways. Perhaps the behavioral monster is latent in many of us and is, under certain conditions, enabled.

Back to the movie.

Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac), arrogance personified, metabolizes his grief at his mother’s death and his fury at his father into a determination to break the ultimate barrier between human and god: the power to conquer death and create life. The point of his efforts seems to be little more than an Oedipal dick-measuring competition. His short-sightedness — ‘I never considered what came after creation’ — echoes the unrepentant tech CEOs who unleashed LLM-based gen AI, treating human-authored works like corpses to be cannibalized for parts.

As tech executives move fast with impunity for the sake of their bottom lines, it’s humanity’s sense of self they are breaking: witness recent news stories about AI-induced psychosis and the withering of mental aptitude that comes with offloading creative, analytical, and emotionally sophisticated activities to ecocide-plagiarism-psychosis machines that vomit pretend versions of human creations. In the words of Jurassic Park scientist Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) on re-creating dinosaurs, they ‘were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should’.

If ‘to monstrify’ (a verb surely due a renaissance) is to tell stories about how someone is supposedly a threat, its inverse is ‘to deify’: to tell stories about how a category-breaker — say, a ‘genius’ or a billionaire — gets to do whatever the hell they want.

Society doesn’t simply enable genius: it invents what it means by genius and identifies who counts as one. Today, the tech billionaire is a stereotypical genius: rather than being held to account for the harms they cause, their every whim is fulfilled, seemingly activating their inner (sociopathic) toddler.

Why does humanity seem so determined to replace itself? The short answer feels like a dead end: an intractable problem hard-wired into the human psyche. That story goes, people are willing to replace human creations and relationships with artificial ones because they are: galactically selfish (venture capitalists and tech executives); short-sighted (incompetent educational administrators chasing short-term cost savings); uninformed or unimaginative (normies who don’t hang out on Bluesky); thinking magically (folks who rationalize their gen AI use for writing, pictures, sound, or video as a drop in the ocean or as an ethical application); lazy (cheating is faster); lacking in self-confidence (only magnified by the myth of the tool and the existential pressures of late-stage capitalism); distressed and isolated (confiding in chatbots); going ‘la-la-la-la!’ with fingers in their ears, hands over their eyes, when any whiff of tech industry critique reaches them; or government bureaucrats frit of numbers throwing the keys to society at tech billionaires who missed the memo on what being human even means.

But this litany doesn’t solve the problem or prevent more of the same in the future (if there is one). The real question is why tech bozos continue to get a pass not just from politicians stuck in a doom-loop of campaign finances (policies that speak to the many losing out to handmaidening for the ultra-wealthy) — but also from everyone else.

Del Toro takes the ambiguity that makes Shelley’s novel so potent and directs it at those who invent or enable both of her monsters, the undead Creature and the sociopathic ‘genius’.

The physicians adjudicating Victor Frankenstein’s disciplinary hearing are appalled by his early demonstration of reanimated body parts. Frankenstein’s arrogance — ‘perhaps God is inept’ — is clear. Yet arms merchant Heinrich Harlander is transfixed. The syphilitic Harlander will bankroll Frankenstein’s experiments in the hope that he will deliver a body into which Harlander’s mind may be transposed, a form of magical thinking he shares with middle-aged tech billionaires so afraid of dying that they talk of uploading their consciousness into the cloud.

Enablers are those who continue to make atrocities possible even after the true nature of actions and their perpetrators has become apparent. Societies create permission structures that enable monstrous behaviours. These aren’t the misdeeds of re-animated corpses but the acts of individuals who break things and wash their hands of responsibility.

Harlander’s niece (and Victor’s brother’s fiancée) Elizabeth Harlander (Mia Goth), unimpressed by Victor’s grandiose promises, nails the problem: ‘Ideas are not valuable by themselves’ and ‘only monsters play god’.

The categories of genius and human are co-dependent, as now are the categories of AI and human. Some people have normalized resource-hogging, theft-underwritten gen AI for use cases where ethical alternatives (like using your own unique, magnificent brain or paying a person) exist. In this sense, humanity feels like a Promethean collective in which some will play with fire in the hope of coming out of the inferno unfried.

Del Toro’s luminous, immersive production fluoresces into view an imaginative precursor to today’s ‘technochauvinism’: what data journalist and professor Meredith Broussard calls the assumption that the best solution for any problem is always technological.

What comes next? That depends on all of us: on actions we choose to take, small or large, to lobby or inform our communities and our leaders and elected representatives, or - if we are one of those decision-makers in education or government who inks deals with corporations - to have the moral integrity to not do a Victor Frankenstein.

More of my words

If you enjoyed this essay you might also like this one about how basement adventures showed me why ChatGPT can only ever be garbage.

If you fancy reading something light and escapist, you might enjoy this essay from deep in the archives, about thinking and reading about whales.

Add a comment: