Vox Populi, Vox Dei

Elon Musk, Donald Trump, an 8th-century Monk named Alcuin, and the importance of historical context.

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

Twitter is a dumpster fire - even more so since it was taken over by Elon Musk. And recently, in a move that surprised very few, he reinstated the account of former President Donald Trump (who had been banned for his role in the insurrection of January 6, 2021). But the way in which Musk decided was… odd. He did it by twitter poll, and then announced the results with the Latin phrase “vox populi, vox Dei” (roughly translated, “the voice of the people is the voice of God”). In common parlance, this of course means that there’s wisdom in the crowd - that the majority should rule.

The original use of the phrase, as many have pointed out, means something different though.

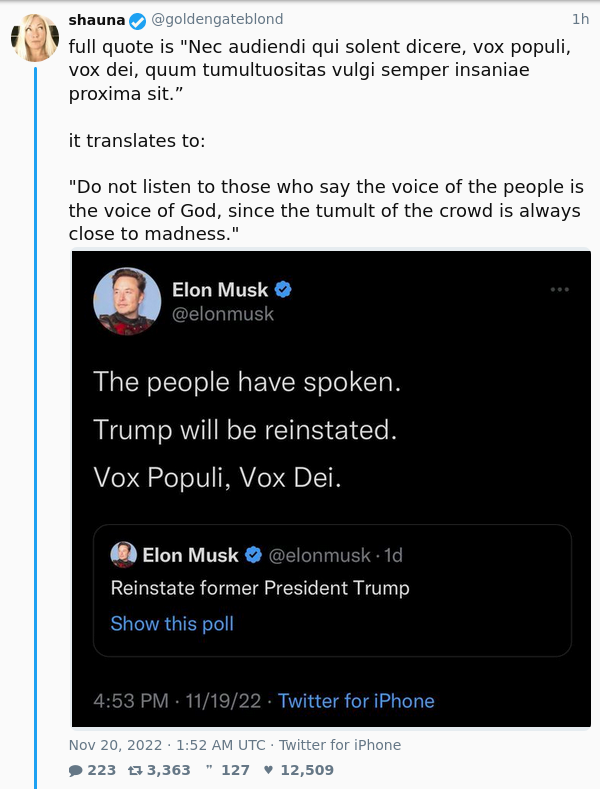

A tweet by @goldengateblond on former Twitter (now deleted but originally posted 11/20/22 at 1:52am) said:

full quote is "Nec audiendi qui solent dicere, vox populi, vox dei, quum tumultuositas vulgi semper insaniae proxima sit.”

it translates to:

"Do not listen to those who say the voice of the people is the voice of God, since the tumult of the crowd is always close to madness."

What’s being quoted against Musk here is a passage from the end of the 8th century CE - in a letter written by the monk and courtier Alcuin to his king Charlemagne. To offer some context, I spoke over email with Dr. Rutger Kramer, an assistant professor of medieval history at Utrecht University and author of a great book on the emperor Louis the Pious.

He told me about the complicated history of the phrase and about the importance of historical context. “Vox populi, vox Dei” does indeed, as far as we can tell, date back to the time of Alcuin, a chief advisor to Charlemagne and a luminous intellectual of the 8th century. In a 798 CE letter, responding to some questions from Charlemagne about how a ruler should act, Alcuin:

“specified that ‘the people should be led, not followed’ (a sentiment we see echoed more often in his letters) and that the ruler ‘should not listen to those who keep saying the voice of the people is the voice of God, since the riotousness of the crowd is always very close to madness.’ This letter is a reminder of the responsibilities of a ruler – to keep the ‘crowd’ at bay by sometimes not giving them what they want because it’s better for them in the end.

This isn’t to say, Kramer emphasized, that Alcuin is saying that a ruler should ignore the “people” (and more on who those “people” are in a bit) but rather that one shouldn’t blindly follow the crowd.

Alcuin (center). Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod.652, fol. 2v (Fulda, 2nd quarter of 9th century)

And yet, that letter from Alcuin only survives in a single manuscript so it’s hard to say how well-known it was even through the rest of the European Middle Ages.

The phrase, as we currently understand it, really traces its roots to the early 14th-century archbishop of Canterbury, Walter Reynolds. In 1327, Parliament met to depose King Edward II and Reynolds wrote a tract/ preached a sermon entitled “Vox Populi Vox Dei.” This seems to have helped tip the balance and forced Edward II’s abdication, and the coronation of his son as Edward III shortly afterwards.

But Kramer reminds us, it’s unlikely that Reynolds meant ALL the “people” when he was advocating. More likely, it was “simply the elites whose voice actually mattered in the context of a late medieval English parliament.” The decision that was being reached in the context of the 1327 Parliament “might be due to an impulse of divine inspiration, but in the end still comes down to a decision by the court.” In neither case - Alcuin or Walter Reynolds - was this an “opinion poll,” even if they do both suggest that there’s more than 1 person involved in the decision-making.

More people in power might do well to heed Alcuin’s advice – being in a position of power/ authority is a RESPONSIBILITY, leading people is a BURDEN.

So, what lessons can we take from this foray into the past? There may be wisdom to be gained in thinking not with the denuded phrase itself, but in reintegrating it to its medieval context. Kramer said “more people in power might do well to heed Alcuin’s advice – being in a position of power/authority is a RESPONSIBILITY, leading people is a BURDEN.” Both Alcuin and Archbishop Walter Reynolds were trying to get their audiences to think about the public good, to weigh what the “people” say but for the leader to also think through exactly who those “people” are.

In other words, Kramer concluded, “the [use of] vox populi shouldn’t be a reason to relinquish responsibility: hiding behind an internet poll is exactly the kind of mismanagement that many a medieval advisor would counsel against.”

Add a comment: