"Medieval" as a Moral Argument

Some thoughts on recent comparisons of 2025 to the "Dark Ages" and a New "Feudalism"

Modern Medieval

by David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele

At the beginning of the year, we spotted a trend among trend spotters - that if people were thinking about the Roman Empire in previous years, 2025 was going to be the year people thought about the Middle Ages. In a piece for Slate about all of this. The design aesthetic of “castlecore” and literary genre of “romantasy,” were for us the evoking the medieval - filtered, really, through a kind of 19th-century Gothic romanticism - as something to be imaginatively gathered into the present.

This is a process that the theorist Svetlana Boym called “reflective” nostalgia - a creative use of the past that understands the distance between “then” and “now” seeks to blend the 2 in hopes of creating a different future. In the case of castlecore/ romantasy, medieval aesthetics are a gendered site of resistance to techbro authoritarianism (as well as the general creep of tech surveillance into all our lives).

But there are other types of nostalgia, other ways to invoke the European Middle Ages.

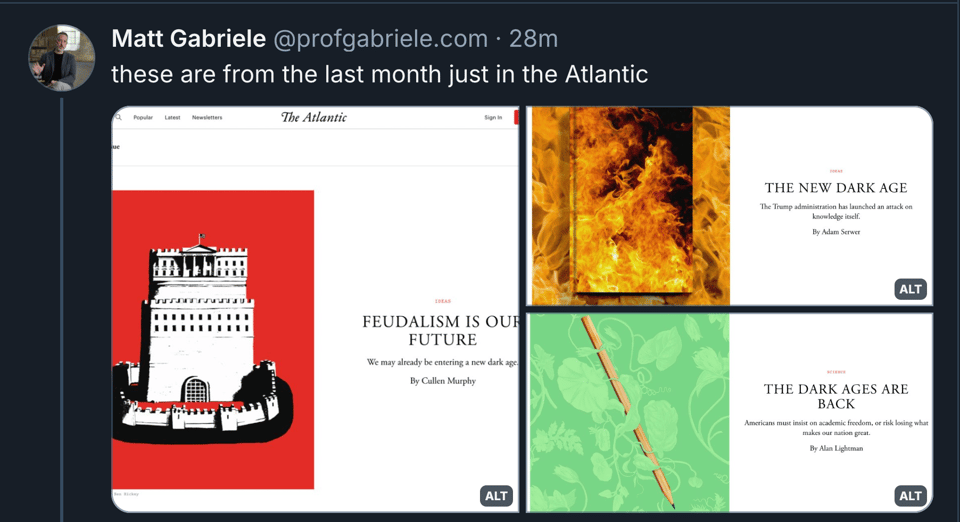

Just over the past month or so, The Atlantic has published 3 pieces explicitly about how the United States (as a “new Rome”) is entering a new “Dark Ages.”

It began with a piece from a physicist, about right-wing attacks on academic inquiry - the “dark ages” were a period without science and learning. Then was followed up by a (generally quite good) piece on right-wing attacks on knowledge itself - again, “dark ages” as a place without literature and learning. And now, a new piece about how “Feudalism is our Future” - the “dark ages” as a revisiting of techbro authoritarianism. In all 3 cases, the 2nd Trump administration is a loss - a “fall” - from a previous “Golden Age.”1

Indeed, directly in this last piece (on what’s elsewhere been called “neofeudalism”), the author argues that despite the Trumpist love affair with ancient Rome, it’s the Middle Ages that have returned. He writes:

With the accelerating advance of privatization, they seem to be moving our way in the form of something that resembles feudalism. Medievalists argue over what that word really means, parsing it with contentious refinement. Was it even understood at the time? Stripped bare, though, the idea is simple enough. In Europe, as imperial power receded, a new system of organization took hold, one in which power, governance, law, security, rights, and wealth were decentralized and held in private hands. Those who possessed this private power were linked to one another, from highest to lowest, in tiers of vassalage. The people above also had obligations to the people below—administering justice, providing protection. Think of the system, perhaps, as a nesting doll of oligarchs presiding over a great mass of people who subsisted as villeins and serfs.

First, this isn’t true - not, like, at all.

“Feudalism” just wasn’t a thing, and “neofeudalism” is even less of a thing. David has written about this, but more recently the scholars David Addison (a historian of Late Antiquity) and Merle Eisenberg (a medievalist) took on the issue in great piece in Jacobin that appeared before The Atlantic article quoted above.

In their piece, Addison and Eisenberg point out that different people mean different things when they say “feudalism” and that these definitions are often mutually exclusive of one another.2 But more important than “fact-checking” historical claims like this, we need to understand that such comparisons aren’t really about the past at all. They write:

the appeal to archaic models to explain contemporary changes is a morbid symptom of an age in which visions of a better future have been replaced with oppressive fears of backsliding and regression.

Or to put it another way, the “feudalism” metaphor lets capitalism off the hook.

All three pieces in The Atlantic, and the broader discourse asking “are we Rome” (no) or “is this the Dark Ages” (also, no) follow this same model of projecting current ills onto the past - of implying that what comes next is “other,” a rupture bound up in the past rather than emerging out of the present.

This type of nostalgia, one that uses the myth of the “Dark Ages” to wistfully conjure a Golden Age of Rome into the present, is what Boym in her essay called “restorative” nostalgia. And restorative nostalgia is a desire to revisit time as if it were place. Restorative nostalgia summons a vision of now-lost truth from the past into the present. It asserts that things were better “back then” and then asserts that the “back then” can appear once more, aroused from its slumber to conquer the present once more. No better example of this than “Make [insert whatever here] Great Again.”

In the Epilogue to The Bright Ages (that we cheekily titled “The Dark Ages”), we show how the “dark ages” term came about - how it was created well after what we think of as the medieval period, how "the particular darkness of the Dark Ages suggests emptiness, a blank, almost limitless space into which we can place our modern preoccupations" (page 251). The European Middle Ages are used, in other words, as a handy catch-all antithesis to modernity. Whatever we are, they’re not. Whatever we aren’t, they are. Actual past be damned.3

We’re absolutely not saying that people shouldn’t use historical analogies. Useful historical analogies lead to further questions, pushing us toward deeper analysis

But evocations of the medieval past - ones dependent on restorative nostalgia - are an argumentative trick, in which the logic is syllogistic rather than analogical. For example, if we agree that Nazis were bad (and we really really should!), then if we can liken something else to Nazism, it must therefore be bad, too. What this is doing is using the past to make a moral argument, as a way to distract from problematic present contexts. Here, we all “agree” that the dark ages are bad, therefore…

In an essay we wrote for The Washington Post in 2021, we said:

Comparisons don’t speak for themselves; that’s the work of history, of those who study the past. It has been said that bad history does violence to the past. Allow us to gently disagree. The long dead can no longer be harmed. The real danger of bad history is that it does violence to the future. The study of the past, at its best, is filled with the potential of prophecy. History, at its best, opens up possible worlds.

This is the opposite of the playful nostalgia of castlecore and romantasy. Those show us possible worlds. “Neofeudalism” and “Dark Ages” discourse robs us of these possible worlds, of our ability as people to make choices and shape our own future.

Boym warned in the essay linked above, “unreflective nostalgia can breed monsters.” And Medieval 2025 is beginning to breed some monsters - some unwittingly waiting, mouths agape, to gobble up our hope in something better on the horizon.

On how Golden Ages are myths - all of them - see Ada Palmer’s great new book Inventing the Renaissance. ↩

The whole premised of “neofedualism” rests on the idea that “public” goods became “privatized” after Rome, with justice/ economics/ etc. falling into the hands of the nobility. The problem is that the nobility was part of the governmental structure and that the very definitions of “public” and “private” are very much modern, capitalist ones. But that’s another essay. ↩

Mateusz Fafinski said it more succinctly "The Dark Ages" violates the rule that historical periods are discretionary but not arbitrary… Calling the period after the transformations of the Roman Empire ‘DA; is a value judgment inconsistent with the evidence.” ↩

Add a comment: